With a thick layer of ice covering the South pole, it looks like a solid fortress. However, scientists have just found scary evidence that this "fortress" is more fragile than we thought.

A new study based on samples collected from the seabed has shown that in the past, the southwest iceberg of the Arctic had completely collapsed, turning the continent into a chain of disjointed islands in the ocean.

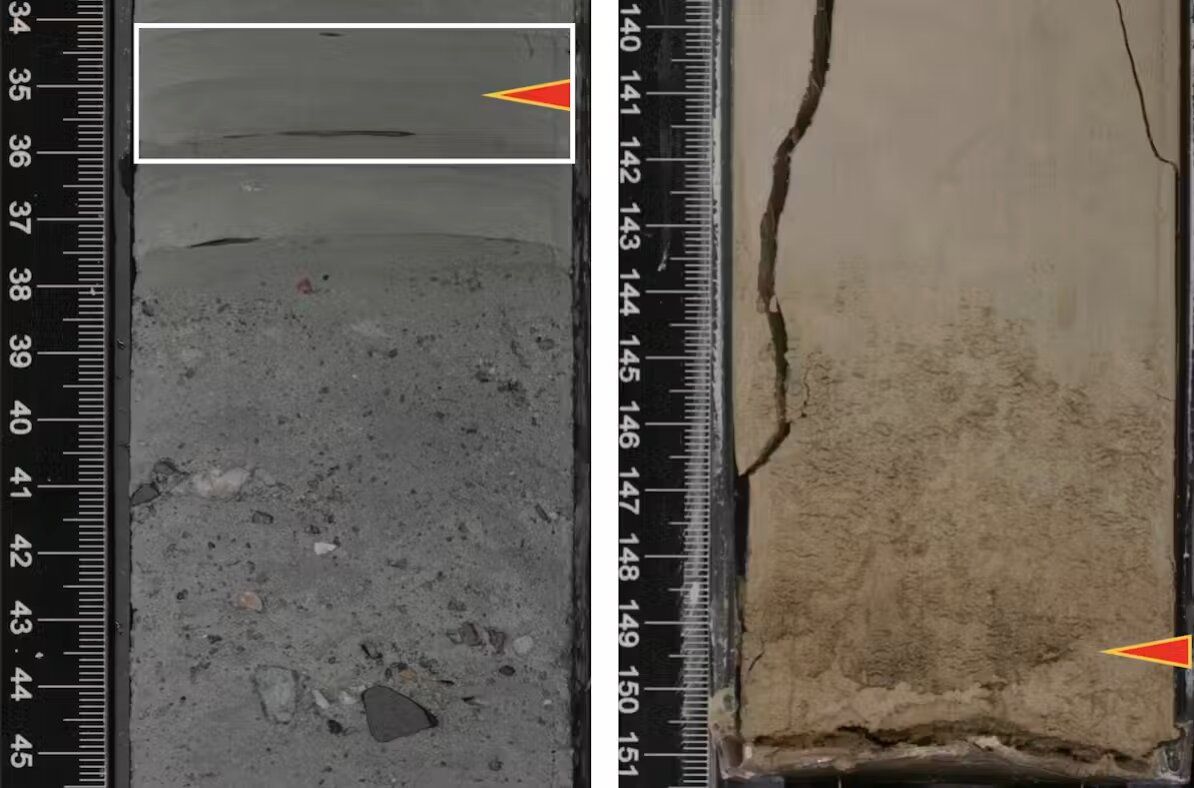

The clue to the discovery of this shocking event came from the exploration of the JOIDES Resolution drilling ship in the Amundsen Sea. Scientists have drilled nearly 800m deep into the seabed to remove "residue" that preserve the history of the Earth from millions of years ago.

The biggest surprise came when Professor Christine siddoway found a small limestone lost in the sedimentary sample. Analysis results show that the stone originated from the Ellsworth mountain range, which is deep inland, up to 1,300km from the drilling site.

The appearance of it at the seabed can only be explained in one scenario: The mountains in the mainland were not completely covered by ice, and the floating ice capes brought soil and rocks moving freely through a large Strait across the center of the continent into the Pacific Ocean.

Subsequent chemical analysis of the ancient mud layers also confirmed the coincidence with the inland soil and rock.

Data shows that during the Pliocene (about 3 to 5 million years ago) - the period of warm Earth similar to today, the southwest iceberg melted and froze again and again many times in just a short time.

The computer model recreated from these data paints a haunting picture of the past: When the ice melted, the Arctic was no longer a seamless continent but became a rugged archipelago surrounded by seas and ice.

The discovery is a burning warning from the past: If the Earth's temperature continues to rise, the geological structure of the South pole will once again collapse rapidly, causing the sea level to rise dramatically globally.