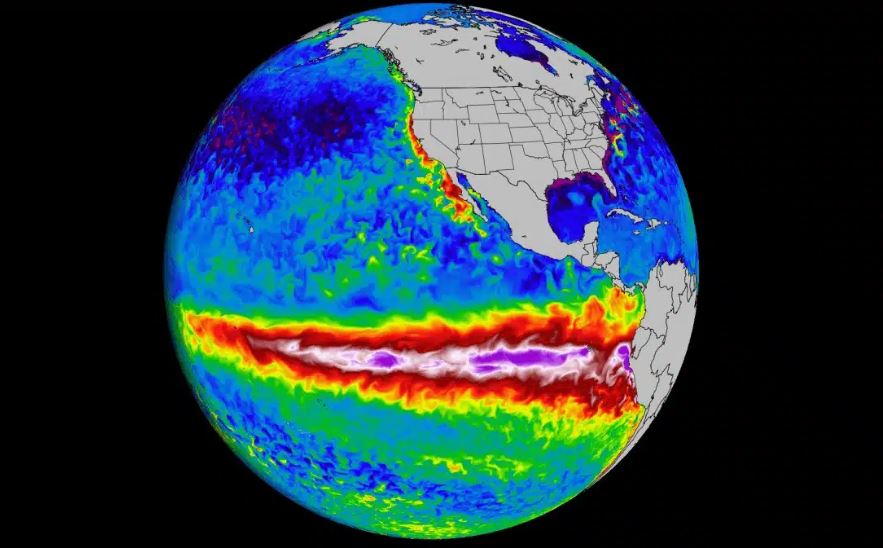

New satellite data shows that La Nina is weakening faster than expected, paving the way for a new El Nino that could disrupt the climate, food and economy of the world from 2026-2027.

In the central Pacific Ocean, under the calm water and beyond normal observation, a large-scale atmosphere-ocean phase transition is accelerating.

Wind direction islands that used to appear sporadically are now becoming clearer, accompanied by increasingly expanding heat anomalies. Climate scientists believe La Nina is collapsing rapidly, while El Nino has just begun to emerge.

El Nino - La Nina, also known as the Southern Hemisphere Oscillation ENSO, is one of the natural mechanisms that has the most profound impact on the Earth's climate system.

When entering the warm phase of El Nino, global rain distribution is disrupted, the frequency of storms, droughts and floods increases in many areas. Although "initiated" from the Pacific, ENSO's impact spreads far beyond all national borders.

The latest data from satellites and ocean buoys shows that a warm water "crash" is forming at a depth of 100-250m in the western Pacific and is trending eastward.

This is considered an early and quite certain sign of El Nino. Many scientists predict that El Nino conditions may appear from mid-2026, with a clear impact in the 2026-2027 climate season.

The worrying point lies in the phase transition speed. In early January, meteorologists recorded unusual strong westerly winds lasting through the western and central equatorial regions of the Pacific.

These signals are reinforced by the combined models of the European Center for Medium-Term Forecasting (ECMWF) and the US Center for Climate Forecasting (CPC).

El Nino is not just an ocean story. When it appears, it restructures large atmospheric circulations, shifts convection zones and changes global pressure balance.

In North America, El Nino usually leads to a more humid winter in the southern United States and California, while Canada and the northern United States tend to be warmer. Atlantic storm activity is often restrained by strong winds.

In the Asia-Pacific region, El Nino is associated with the risk of prolonged drought and heat waves. Australia and Indonesia often bear great pressure on water resources, reduced monsoons and the risk of wildfires. For Indonesia, this impact can spread to the energy and mining sectors, affecting strategic commodities such as nickel or bauxite.

South America is also not outside the vortex. Pacific countries such as Peru and Ecuador often suffer unusually heavy rains, causing flooding and agricultural damage, while the Amazon rainforest may be drier, increasing the risk of forest fires.