Over the past decade, technological innovations such as gene decoding have allowed scientists to take a closer look at cancer cells and their genetic abnormalities. This helps them design vaccines that target more specific targets. At the same time, researchers have learned more about the immune system and how it recognizes and kills patients' tumors, says immunologist Stephen Schoenberger at the La Jolla Institute of Immunology in San Diego.

Nina Bhardwaj, a criminologist and medical oncologist at Icahn Medical School in Mount Sinai, New York, said the research on the cancer vaccine is still in the preliminary stages. However, initial results from clinical trials testing dozens of vaccine candidates against many types of cancer seem encouraging, she said.

What is the cancer vaccine?

The purpose of all vaccines, whether a cancer vaccine or a COVID-19 vaccine, is to educate the immune system and provide the goal that needs to be identified and destroyed to keep the body safe. The COVID-19 vaccine teaches the human immune system what the SARS-CoV-2 virus looks like so that when the pathogens become infected, immune cells can quickly locate and kill them. Similarly, cancer vaccines let immune cells know about the shape of a tumor cell, allowing them to search for and destroy these cancer cells when they appear.

The ability of cancer vaccines to teach the immune system is a difference from other immune therapies that use therapeutic agents such as cytokine protein and antibodies, and include strategies such as changing patients' immune cell genes to fight cancer.

Some cancer vaccines rely on removing immune cells called thorn fees from patient blood samples and exposing them to important proteins collected from the individual's cancer cells in the laboratory. These educated cells are then returned to patients in the hope that they will stimulate and train other immune cells, such as T cells, to detect and kill cancer.

But the vaccine does not provide the quality and quantity of T cells needed to remove large tumors, Bhardwaj said, adding that it is best to vaccinate when the tumor is still small.

To increase the effectiveness of the vaccine, researchers often combine it with drugs that help boost the immune response to this tumor.

vaccine manufacturers are increasingly relying on mRNA technology, which is also used to create a COVID-19 vaccine, to instruct the thorn cells in the patient's body to create proteins or peptides specifically for tumors that will create an immune response.

Some vaccines have a preventive effect because they teach the body to kill viruses that cause cancer such as hepatitis B and human papilloma virus, thereby preventing infections that can lead to tumors.

How do scientists create a cancer vaccine?

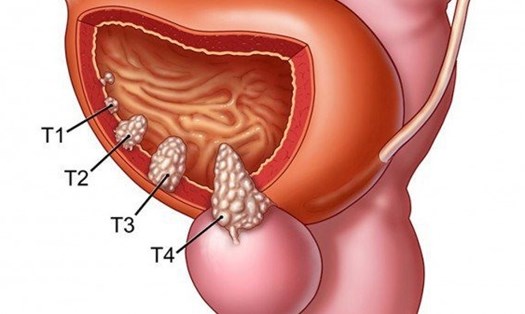

All cancer vaccines rely on protein, known as antibodies related to tumors, a protein that triggers an immune response when it is more present on the surface of cancer cells than healthy cells or exists abnormally or suddenly. When T cells see these ancient trees, they recognize the cells as cancer and destroy them.

Cancer biologists identify these tumor antipods using sophisticated Sequence technology that helps detect specific differences between DNA or RNA of healthy cells and cancer cells. Schoenberger says the trick is to understand which breakthroughs will create a T cell reaction and will become a good target for the vaccine.

His team selected antibodies based on patients' reactions to cancer. By studying T cells in their blood samples, we are looking at what the patients own immune system had chosen from the tumor- manifested pathogens for targeting, Schoenberger said.